A recent study from Stanford University took pains to empirically prove that there is a significant bias among teachers when disciplining students from diverse racial backgrounds. The study, performed by Jason Okonofua and Jennifer L Eberhardt and chronicled in the journal Psychological Science, tracked discipline responses from 57 current teachers based on fabricated discipline referrals.

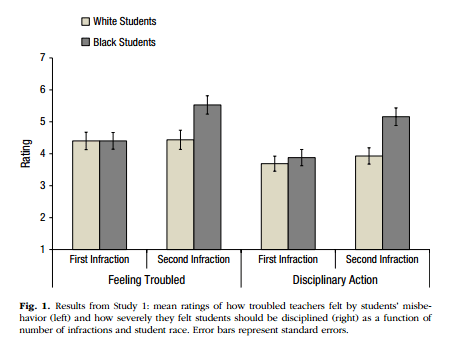

In the study, teachers were randomly given reports of student misbehavior and asked to rate the child as “troubled.” In a second experiment, the teachers were asked to decide whether to suspend the student from school based on their behavior.

Each report was assigned to a student name that would artificially assign the student a race. According to the author, “We manipulated student race by using stereotypically Black (Darnell or Deshawn) or White (Greg or Jake) names.” After receiving the discipline report, teachers were asked, “How severe was the student’s misbehavior? To what extent is the student hindering you from maintaining order in your class? How irritated do you feel by the student? and How severely should the student be disciplined?”

Initially, there was little difference between students who had stereotypical White names and stereotypical Black names. However, when teachers were presented with a second discipline report with the same name from each student, they were much more likely to believe the student identified as Black to be “troubled” and were even more likely to suspend the student from school.

As educators, we have a responsibility to take a hard look at our implicit bias and do what needs to be done to eliminate them.

This study provides further evidence to support a long-held belief, that a student’s race can play a significant role in how they are treated in school. Minority children are exponentially more likely to receive discipline consequences and be suspended from school for misbehavior than their White classmates. This study helps to prove that this problem has little to do with actual levels of misbehavior, and much more to do with inherent bias among educators.

The solution is certainly not simple. One significant step would be to rethink school discipline in general. Perhaps all children, regardless of race, should spend less time “in trouble” and more time figuring out how to function within their community (i.e. the school). This would require teachers and administrators to stop slamming kids with meaningless detentions, suspensions, and other disciplinary measures and replace it with a system of restorative justice and reconciliation designed to integrate kids into the classroom, rather than remove them from it.

This is hard work. But it needs to be done. The current study adds to a growing body of evidence that minority children (whether they be minorities of ethnicity, gender, sexual preference, religion or economic status) face a cornucopia of challenges each day when they walk on campus. The bias of people tasked with caring for and educating them should not be one of these challenges. As educators, we have a responsibility to take a hard look at our implicit bias and do what needs to be done to eliminate them. This will do more than just help our schools, it will help to quell the rampant school to prison pipeline in our country. Again, to quote the authors,

“Racial disparities in discipline are particular problematic because they contribute to the racial-achievement gap, increase the likelihood that Black students will drop out of school, and may then increase the probability that such youths will be incarcerated.”

Too often, we get bogged down with the challenges our students create in our classroom. Rarely to we take the time in those moments to consider the challenges these same children bring with them to our classroom. Perhaps if we did, we could stop labeling kids, and start helping them.

For more on this study,

Psychological Science. Okonofua, Jason A and Jennifer Eberhardt; Two Strikes: Race and the Disciplining of Young Students. May 2015. Vol. 26(5) 617-624.