Schools and school leaders spend a lot of time thinking about many crises in education, but many of them focus on student trends: test scores, changing demographics, declining literacy rates and the like. But there’s another crisis that few people on campuses around the country focus on: changes in the teacher workforce. Ignoring this crisis is to the peril of students in all schools. As these changes continue to grow—and they will continue to grow—the negative impact on classrooms will become more apparent than it already is today.

In an October 2019 presentation to the Consortium of State Organizations for Texas Teacher Education (CSOTTE), the Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath shared some troubling statistics about workforce trends among Texas’ teachers. It’s always dangerous to extrapolate national trends from Statewide data, but similar trends have been cited by researchers at universities around the country and even the US Department of Education.

The most troubling statistics?

- 1 million teachers quit every year

- A growing number of those teachers aren’t quitting to go work at another school; they’re quitting teaching altogether.

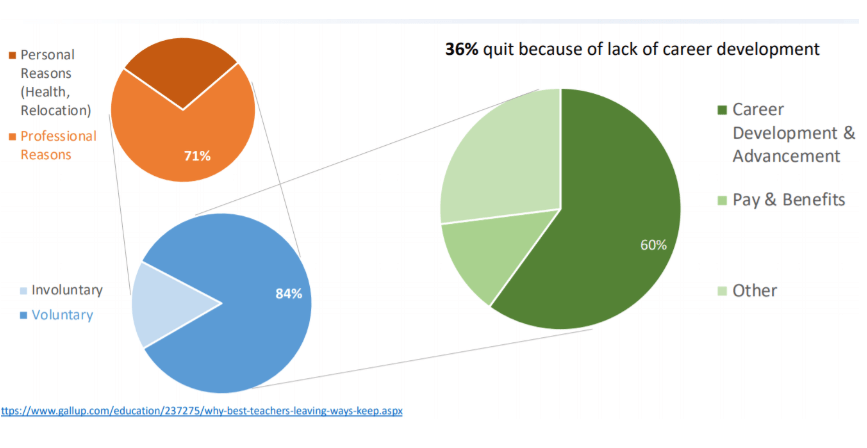

- 36% who quit, do so because they feel no career development opportunities exist for themselves.

Of course, with a total workforce nearing 4 million, it’s natural to see a large number of people quitting any job. However, the fact that so many, almost 300,000 teachers, are leaving the profession primarily because they see no opportunity for professional growth is troubling.

These trends are worrisome enough, but become even more worrisome when coupled with some additional statistics about the next generation of teachers.

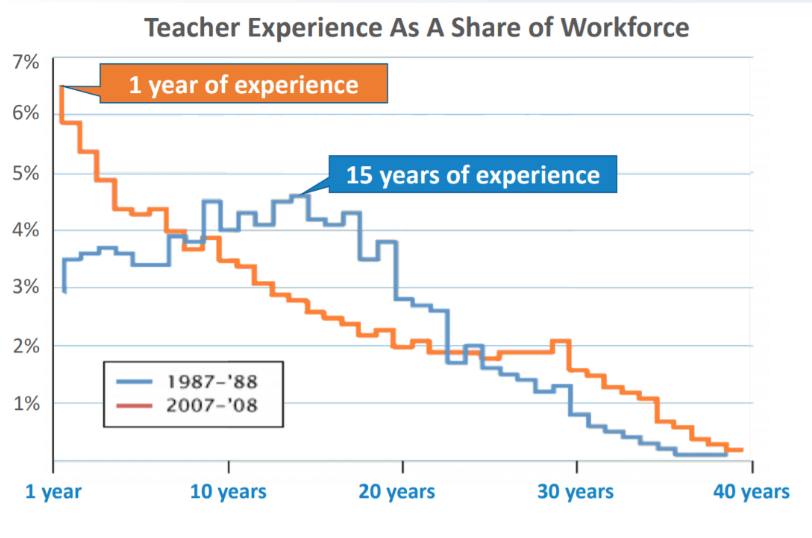

The average teacher has fewer years of experience in the profession than they have in decades.

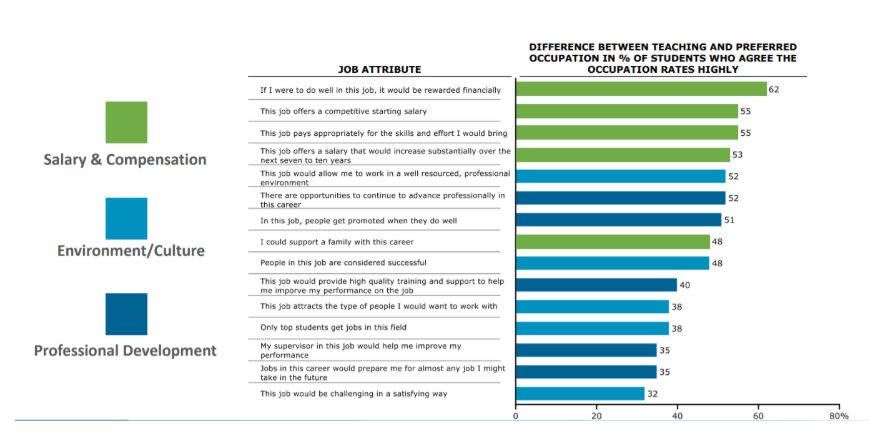

Teaching as a profession is not popular to young Americans considering their future careers.

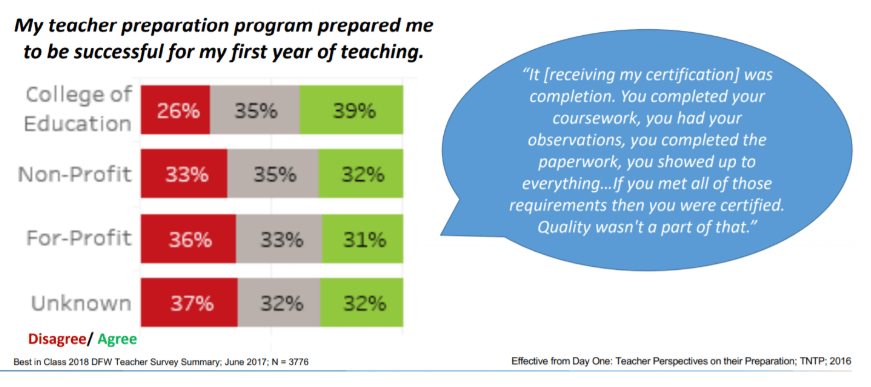

And 2/3rds of those who do pursue careers in teaching feel they are unprepared to do their job.

This is a perfect storm. The confluence of a growing population of disaffected teachers and a shrinking population of young people who are excited about and prepared for a life of teaching has two major consequences for schools:

- The teacher shortage is going to grow dramatically. In fact, the Department of Education has estimated that the shortage will be in the hundreds of thousands by 2025. That’s hundreds of thousands of classrooms with no certified teacher in them. That’s millions of students crammed into already overcrowded classrooms. That’s hundreds of thousands of already overworked and disaffected teachers picking up the slack.

- The professional growth opportunities schools provide will become even more important. As more and more people choose an alternative path to teaching, many set foot in a classroom on day one with little formal training and no practical experience at all. This means that the fundamentals of teaching, a job previously relegated to universities and other teacher preparation programs, will now fall to schools.

So here’s the crisis: many teachers feel they are either unprepared or have little opportunity to develop new skills. Those who do feel they have learned new skills see no chance to be rewarded for those new skills. And they leave. Or, sometimes worse, they stay…unskilled and disaffected. The consequence is dire: we risk children being taught by people who don’t know how to do their jobs, are disgruntled about their jobs, or both.

And at the center of all of this is one part of education that gets, for the most part, a cursory glance and rhetorical support from most school leaders: teacher professional development.

And what do most schools do about it? They wring their hands and develop more of the same kinds of PD that they had before! Schools develop a larger quantity of one-time workshops that are measured only by attendance, they try to make PD workshops “fun” for teachers, they pay more consultants to come in and do large one-size-fits-few events, they change the name of department or grade level meetings to “Professional Learning Communities” with no substantive changes to the content. What don’t they do to develop teachers? Look to their most important asset: their teachers.

Much the same way that students should be at the center of all lesson planning, teachers should stand at the center of all professional development efforts in a school or school district. Not hypothetically, but actually. Teacher skill data should inform all planning. And the actual teacher expertise of any organization should be the locus for all support. All teachers do something well, and no teacher does everything well. By building opportunities for teachers to connect with one another in small groups based on their needs and strengths, share with one another, and be rewarded for that sharing, schools will give teachers a chance to grow and feel a sense of validation for that growth (rather than the silly certificate of attendance that arrives at the end of most workshops). There’s plenty of money for it. Schools spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on consultants and PD presenters each year. A simple reallocation of funds can distribute those dollars to teachers who contribute to their own and others’ learning. Some innovative schools are doing this already. And many teachers are as well. Entire ecosystems like Teachers Pay Teachers have sprung up to fill this void left by the institutions who are actually tasked with supporting teachers. Rather than leave these ecosystems to chance, schools should invest in them internally so teachers see an institutional recognition of their needs and growth.

Will this solve everything facing the coming crisis in the teacher workforce? Probably not. But is it better than what most schools are doing today? Absolutely.

A return to the lessons of the past, improving where we understand:

My peers and I are so fortunate to have grown up when we did, while America education was still number one in the world, and as a teacher, I sought to improve upon what I had learned as any good teacher will do, but also utilize the wonderful experiences and insights of my former teachers. They taught reading and writing well, my mathematics was encouraged, and we learned responsibility if we didn’t wish to keep visiting the principal’s office or remain in the same grade, some going to summer school to finish what they hadn’t completed. Having gone to several schools, having a variety of committed teachers, I learned, but also learned to think for myself, for it would be through my efforts, sometimes with friends, that I would get better grades. And in middle school, when I finally earned honor rolls, I knew I had done it. Putting in the work, I set myself for the future, for I knew I could learn anything if I put my mind to it. After a few years of working in different fields, as some of my peers, returning to college with an understanding was very helpful.

As a teacher, I knew the importance of teaching writing, but also the importance of challenging the kids in both grammar and thinking. In their essays, I would ask how they arrived at conclusions. Was it through personal experiences, which they need to relate, from other authors, which they need to cite, but also what it their understanding. With projects and both history and science, I sought to teach them cause and effect. Reasoning. And if the realized something I hadn’t, I wanted them to share. Discussion in classes, as I see it, is very important, both to open the lines of honest conversations, but to teach debate in a civil environment. Sometimes I challenged, sometimes I didn’t to encourage the quieter kids to participate.

As I see it, school encompasses teachers who have both an education but also practical experiences. Teachers are the ones who think for themselves, want the kids to be responsible and also think for themselves, and hope the little ones grow up as fine young men and ladies, ready to take on responsibilities for the next generation. Some of the more interesting conversations, though I taught the higher grades in elementary and middle school, was with the little ones (siblings and those who wandered our way, even on the bus) who already knew what they wanted to do. Delightful conversations. A couple were very insightful at such a young age, and I could only imagine the conversations they had with their parents.

Life is good. But there was something magical while growing up. Playing outdoors, getting into trouble, digging through the dumpsters for bicycle parts and carpets for our tree forts, creating games. Our teachers sometimes had inventive projects, and we had vocational electives, and they left it up to us to find what we wanted to be, though we had a few career people show us other options. Like my father said, he never knew what I would do but figured I would figure it out (In the mean time, I had chores, mowed neighbors’ lawns, and took on a few part-time jobs.). Perhaps, that was a great gift. Letting me figure it all out while he worked and provided, my parents always there.

With time, we read more and more, learning about history and the difficulties of the past. There’s an old saying, that those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it. Many of those lessons are here, today. The difficulties we see were demonstrated by countries past and present, but also predicted by the founding fathers, both federalists and anti-federalists discussing their concerns as well. We can learn so much from many who endured those difficult times, those who endured the world wars and cold wars, and those who experience first-hand the grueling experiences of a people who don’t understand cause and effect and the search for real understanding. Theory is always good to discuss, but practical experiences and lessons are perhaps more important.

For students in my class, I would always encourage them to think for themselves. With some things, that’s easy. In others research. And in still others, a lifetime of research. But in this, thinking for themselves, they learn to question what they read and hear, but also to encourage the same in their own future children after they grow up and get married. Then, the next generation continues learning and discussions within families and friends, even neighbors, and this becomes a dynamic for improvements. We are what we do and what we set as an example.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you considered the reasons why we’re losing teachers and why we are moving away from what made America number one in the world?

LikeLiked by 1 person

What metric are you using to define number one in the world? By international school ratings? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

LikeLike

Actually, that’s information you can research, but that wasn’t the purpose of my comment or sharing. However, when I look back, I remember the classes in general, but also some of the lessons that caught my eye. But more so, I remember always being held responsible for my own work. The teacher taught, and we were to do the work. Our parents told us to finish our homework. And when I got lower grades (Once, I was held back, but that was partially due to starting school early.), I heard it at home. These simple lessons of life made the difference.

LikeLiked by 1 person